Juniors: A Year Later Pandemic Reflections

Ryan Elly

Although for most people last spring was a rough time, I share a completely different perspective. During that time I had a group of friends of around ten or so people in it and for me, it was an experience that I wish I could go back to. We would all be on the same horrific sleep schedule where we would wake up in the middle of the afternoon and join what’s called an Xbox party, which was like a group call. We would play the same game all the way until sunrise and repeat the process for almost two months. Every day we each grew more and more competitive, which resulted in all of us getting better and overall just having more fun. I know the idea of being stuck in your house was miserable most of the time, but when we would play we would lose track of time and it really didn’t seem like we were trapped inside our homes for an extended period of time.

Colin Kind

Nearly one year ago today, the world shut down. Masks were being bought from every store, people scrambled just to get some toilet paper, and the world was in shambles. When we got word that school was shutting down for six weeks, I was finishing up baseball practice. I was really shocked because I didn’t expect the school to be shut down for six weeks; I thought it would only be a couple of weeks and then everything would be over.

But nearly a year later we’re still at home, doing Google Meets and learning through a computer in our rooms. I’ve learned many lessons over the past year like how to manage my time and just how delicate time really is.

Many memories were made throughout quarantine, memories that will last a lifetime. Throughout quarantine, my family and I would play games like Monopoly, Uno, and I even learned how to play different types of card games like Texas Hold ‘Em and Spoons. Some of the most memorable times were when we ended up staying up until one or two in the morning working on puzzles as we passed the time being locked in our home.

Sometimes I think about what it will be like to tell my future kids and grandkids about this past year. I will tell them how as a teenager I was barely able to go anywhere for an entire year, and if I did, I had to wear a mask. I will describe for them the constant worries and fears I had about contracting Covid and transmitting it to others, including my parents.

The world has changed so much in just a year.

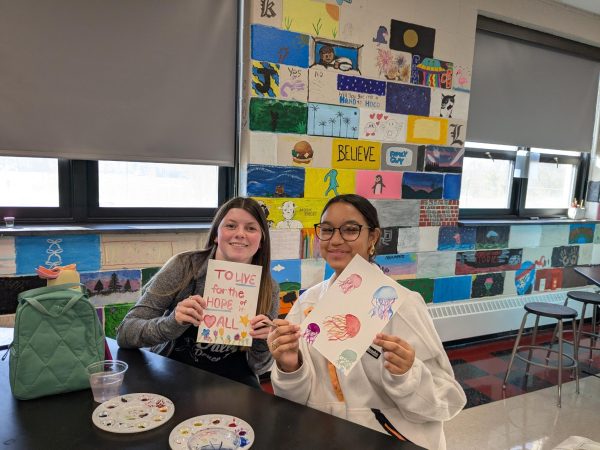

Grace Coller

Friday, March 13, 2020. Oddly enough, I remember bizarre details about the day with stunning clarity. I remember walking to the bus stop early that morning, and as I was waiting, I had a feeling of uneasiness that I couldn’t quite pin down. The day felt weird – almost apocalyptic in a sense – I would only later find out why. I remember talking to my friends at lunch about how the mysterious virus had been spreading in New York City; the whistle-blower doctor in Wuhan had just recently passed away. I remember when the cases in the United States could be counted on one hand. Now there are over 29 million cases. I remember all of us getting called back to our homerooms the afternoon of that Friday – the hallways packed with students in a way that has since been unmatched. In this “emergency homeroom,” we got additional Google Classroom codes and were told “nothing was certain” – whatever that meant. I remember school being loud, buzzing with uncertainty, and a school’s-out-for-summer kind of feeling. I remember going to the store that Friday night with my dad and waiting in a line that wrapped all the way around as people rushed to buy essentials in a storm-is-coming way; what ensured was not a storm – it was a hurricane. That trip to the grocery store was the last place I went without a mask, and ironically, it was the most crowded I have ever seen it.

On top of everything else, I remember getting that phone call from the school, informing us that in-person learning would be suspended for the next five weeks. At the time, by the beginning of April, we’d be “back.” My family and I were over at my grandmother’s house eating dinner with my cousins when we found this out. We had just picked up my sister from her friend’s house. I remember the daily rush: getting picked up from track, helping my mom after school in her classroom, sitting down for dinner before my siblings had to be taken to soccer practice. I didn’t realize all of those things would soon be wiped out indefinitely. COVID-19 was still something distant and unknown. Yet no amount of apprehension on that dreary Friday would prepare people for the realities of the upcoming months. For the students of Cinnaminson High School, March 13th was the beginning of a new, unsettling chapter that would forever leave its mark on their high school experience.

In the spring, there was this hope, I suppose one would call it, that we could “flatten the curve.” That we could “stop the spread” before it got out of control. There was even this idea that maybe, within the next three months, it would “go away.” As masks first became prevalent, everyone had something to say, but no one really knew the answer. In order to purchase groceries online, my mom had to wait up until three in the morning, refreshing the page, just to get a pickup time slot. Disinfectants were literally impossible to get – online, in-store, anywhere. In fact, cleaning supplies of any kind were nearly impossible to get a hold of. The world was simply turned upside down. Daily things became distant, and previously foreign things like wiping down one’s groceries or hunting for hand-sanitizer filled the void left behind by the absence of normalcy.

At the very beginning of lockdown, I was antsy. I felt trapped. I missed stores and restaurants, and I longed to do something. Never before had I spent weeks remaining in my home. Like many others, I tried my hand at baking (which, I’ve realized is a talent I certainly do not possess), I rewrote all of my math notes from the year, and I even did a 2,000-piece puzzle. I found ways to try and fill my time and realized that’s all I was doing: time filling. Like so many others, in the beginning, I felt lost, not only in the uncertainty of the global pandemic but also in the lack of routine. My “to-do” list was empty, which is not a great way to stay motivated. I found myself fabricating jobs to do, simply to keep myself busy. I genuinely cannot explain it, but one day this shifted. In the turn of the seasons, from spring to summer, I suddenly no longer felt so antsy. My routine, or lack thereof, was starting to take shape. It wasn’t that I had more to do – because with the end of school my schedule definitely opened – but instead, I think I was becoming more comfortable with the lifestyle. I came to the realization that in the beginning, I was scared of all the change: I was scared of the pandemic, I was sad that school shut down, I was disappointed that I couldn’t see anyone outside of my house. And these things were all still true, but there came a time when I embraced this new existence, rather than denying it.

Something that really helped me in this transition from rejecting to accepting was the idea that this chapter is a very small part of a much larger story – and this is a story that unites everyone in this world. In other words, no matter how long “the pandemic” lasts, it is a blip on the screen in history. While some aspects may continue to change our lives seemingly forever, the intensity, the challenges, the uncertainty, and the confusion of the present moment cannot, and will not, last forever. COVID-19 is a global crisis. While that at first may seem like a cause for additional stress, it also had a unique unifying effect: this is something that everyone knows, everyone will remember. It is something that is not just preserved in my mind, a part of my life, but instead a part of our collective memory, as a community, as a country, and the entire world. This unparalleled togetherness, as an abstract concept, helped me remember that my place is small. And as such, I realized that I should indeed take my place, and accept it, rather than recoiling away from the unknown.

School in the spring of 2020 was a whole different experience entirely. Unlike this fall, which had been dominated by synchronous, whole group instruction, the spring was quite a free for all. I am fully aware that teachers and administrators were trying very hard, especially when it came to honoring the CHS seniors who wouldn’t get a chance to go back to their high school before heading off to college. However, despite the effort put in by the school district, the spring was intense. There were many times where I had just wanted to give up; I simply couldn’t keep looking at the screen all day. My eyes hurt, my head hurt – I didn’t want to keep looking at the computer. Some days, this made me feel completely overwhelmed. When Spring Break was taken away last year, it was severely disappointing. I understood the logic, but sometimes a break has more value when it is in the middle of a stressful experience, rather than just extra days tacked onto summer. This is just a personal thing, but I’m not usually glad when the school year ends; yet, last year was certainly an exception.

What did we lose from the pandemic? It’s hard to quantify the experiences lost because the world shut down. Without events such as a traditional graduation, senior trip, prom, senior night and much more, the Class of 2020 certainly lost a sense of closure and the opportunity to make those lasting end-of-year senior memories. Without school, or sports, or visits, or concerts, we lost connections with others. I know from a personal standpoint, as the world locked-down, it was easy to go along with it: initiating some kind of alien, online environment to socialize was just not the same. Without end-of-year events, or even getting the chance to talk to most of their teachers, students lost every sliver of a “normal” school experience. Without a chance to say goodbye to their classrooms, their colleagues, or their students, retiring teachers lost that experience of finalizing their career at CHS. On top of all that was lost, though, the biggest thing that COVID-19 took was lives. The count that was supposed to be “flat” soon evolved into exponential growth. Healthcare workers, overworked and exhausted, reported a level of death under their watch that they had never before experienced. Families of over 500,000 people, mourn the loss of a person who one year ago did not have this deadly virus as something to worry about.

Yet, despite this loss, despite this pain, the pandemic did have some silver linings. While the experience was different for everyone, I know the lockdown, and subsequent use of remote learning, has allowed me to be more introspective in a sense. Frankly, I spent more time alone than I ever had before, and spent much more time with the same small group of people. I think that unique experience acted as both a mirror and as a measuring stick. A mirror in the fact that I was able to see who I was reflected more in my daily life. Without a rushed schedule or a forever-long to-do list, I was able to do everything with a greater understanding of why. I questioned: why do I do the things I do? What does this add to my day? To my life? Does this make me happy? These questions are ones we never really get a chance to answer with the mayhem of everyday life, yet the experience of lockdown allowed me to see myself reflected in this way in the things that I did. Additionally, the lockdown acted as a measuring stick as to how we all fit together in the world around us. It was not as much about finding myself, as it was about finding my place. As many have explained, the pandemic put things in perspective; it measured experiences, problems, etc. not independently, but rather comparatively. And while a comparative analysis of daily life may seem too analytical, it has a soothing effect for me, highlighting what is important. In a paradoxical way, despite the confusion brought about by the pandemic, it also helped me find a sense of direction.

Recently, after the high spike in November, increasing cases in December, a subsequent decrease in cases in January, and a plateau of sorts in February, there seems to be a push for relaxed protocols. I want the pandemic to be over too – I completely do. However, we can’t just convince ourselves that it is, simply because we want it to be. Even with vaccines, which have been immeasurably beneficial in stopping the spread, medical professionals are urging people not to relax all protective measures. There seems to be a glimmer of light on the horizon that – perhaps – this might be “over” soon, yet we cannot throw this away by letting our guard down prematurely. As highlighted by the initial spread last March, it does not take long for this virus to infiltrate not only our population, but our way of life. With new variants of the virus, the fight is far from over. While I am not a medical professional, I think it is safe to say that if we continue with protocols and continue to work hard to try and prevent COVID-19 from spreading, it will yield promising results. Yet, if we get swept away in the joy that the pandemic is over and throw away the precautions we so carefully put in place, we are only going to sabotage ourselves. I’d like to put it in writing: today, there have been 124,338 new cases in the United States. There has been a total of 28,937,762 cases in the U.S. with 524,695 deaths. These numbers are incomprehensible, yet memorable.

Time in the pandemic is literally warped. Experts say time is relative, and nothing highlighted the relativity of time more than the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus was moving so fast, the world was a hectic whirlwind of trying to slow it down, trying to mitigate the damage. Time was unforgiving. Yet, in our homes, each day was indefinite. When did one day end and the next begin? The monotony lacked rhythm. It wasn’t necessarily a routine, but more of an elongated existence: one day bled into the next, bled into the next. The days were differentiated the most by the labels on the calendar, rather than the daily activities. During that initial five-week span, time was slow, as I counted down the days until it would be safe to return. But, as that safety was pushed farther and further away, time seemed to move faster and faster. Before I knew it, it was July: what had I even accomplished in the last four months? It wasn’t that I did nothing, but everything was so analogous; the checkpoints of time that typically separate our life into a collection of memories were missing. Rather than a series of distinctive memories, I remember the spring of 2020 as one big swarm of experiences swirling together. But if time is relative, then perhaps reaction is relative as well. In other words, we may not have been able to slow down time to stop the pandemic, but maybe we can take what we learned and react in a more knowledgeable fashion. I think we are defined most by our experiences, our memories, and thus our stories we share. Hopefully, this shared experience of COVID-19, no matter how different our individual memories may be, will act as a foundation for a stronger, more united global story.